And then there is the Russo-Ukrainian War, the conflict with the most potential to escalate into a nuclear exchange. In The Clash, Huntington argued specifically that the future relationship between Russia and Ukraine would serve as a test of his theory. He rebutted John Mearsheimer’s claim that the two countries were headed for conflict because of a long, undefended border, a history of mutual enmity, and Russian nationalism. “A civilizational approach, on the other hand, emphasizes the close cultural, personal, and historical links between Russia and Ukraine and the intermingling of Russians and Ukrainians in both countries, and focuses instead on the civilizational fault line that divided Orthodox eastern Ukraine from Uniate western Ukraine, a central historical fact of long standing,” Huntington wrote. “While a statist approach highlights the possibility of a Russian-Ukrainian War, a civilizational approach minimizes that and instead highlights the possibility of Ukraine splitting in half, a separation which cultural factors would lead one to predict might be more violent than that of Czechoslovakia but far less bloody than that of Yugoslavia.” Here as elsewhere, the civilizational approach proved demonstrably, even catastrophically wrong, highlighting the limits of a perspective that overemphasizes the role of culture in world affairs. Putin might eventually conquer some of eastern Ukraine, but that occurrence wouldn’t result from some civilizational kinship. “By May 2022, only 4 percent in Ukraine’s east and 1 percent in the south still had a positive view of Russia,” according to an analysis by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Amazingly, people who had called themselves Russians living in Ukraine are now patriotic Ukrainians. “Cultural and historical preferences have also changed dramatically. Sixty-eight percent of respondents from the south and 53 percent from the east now describe Ukrainian as their native language,” the Carnegie analysis found, consistent with other studies. These evolutions illustrate how cultural identities are far more malleable than Huntington suggested.

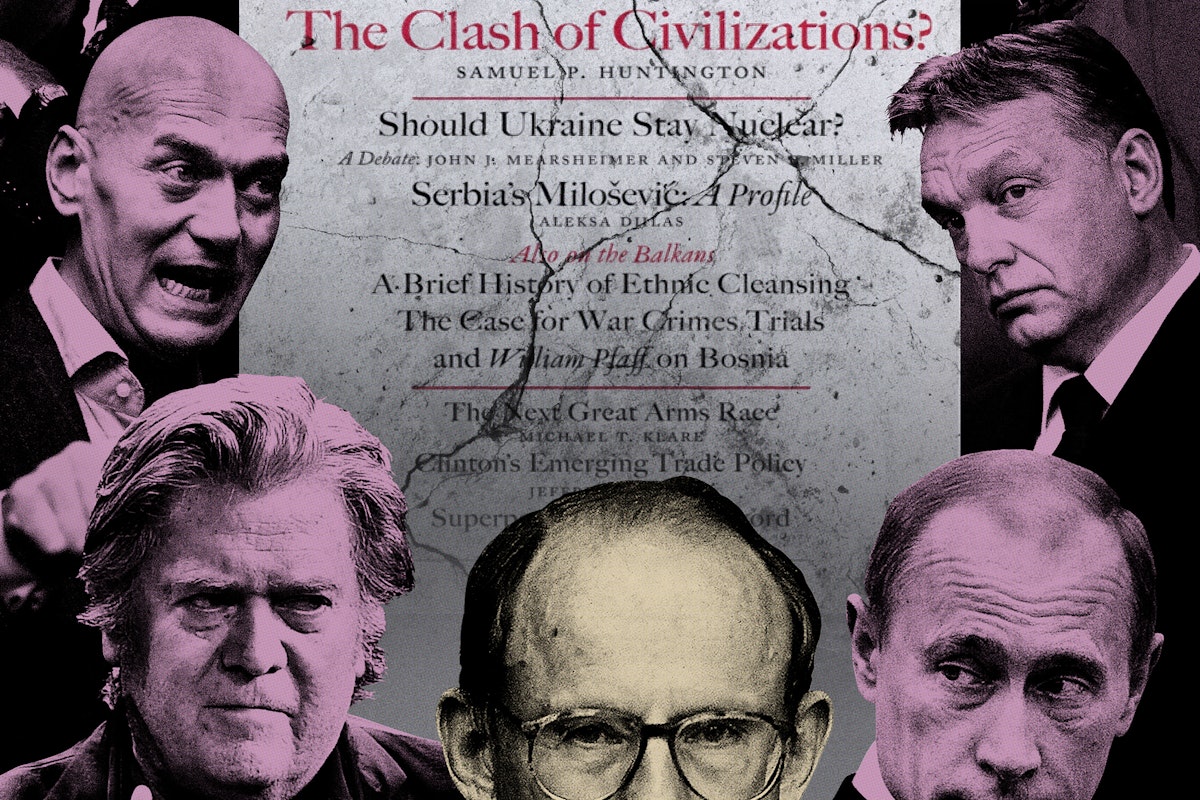

But even as research and events have discredited Huntington’s argument, it has found important adopters among the far right worldwide. Steve Bannon, the influential adviser to the Trump administration, has adopted variations of the ideas, saying, “If you look back at the long history of the Judeo-Christian West struggle against Islam, I believe that our forefathers … kept it out of the world, whether it was at Vienna, or Tours, or other places.” No wonder that Trump’s White House extensively limited immigration, singled out Muslim refugees as primed for violence, overstated the threat posed by jihadist terrorists, and made defending an apparently embattled American civilization fundamental to its worldview.

Beyond the United States, right-wing figures globally increasingly used the language of clashing civilizations. Pim Fortuyn, a pioneer in the far-right populist crusade against Islam, represented himself as “the Samuel Huntington of Dutch politics.” Russian leader Putin styles himself as the defender of Christendom, saying “Euro-Atlantic countries” were “rejecting their roots,” which included the “Christian values” that were the “basis of Western civilization.” Viktor Orbán, the Hungarian prime minister who has become the de facto leader of Christian conservatives, told an American conference of right-wingers that “Western civilization” was under attack by people who hated Christians and globalists who “want to give up on Western values and create a new world, a post-Western world.”