Yarvin’s term for those who rule the modern world is “the Cathedral” (though he has been known to slip into talk about “dark elves” and “hobbits,” too). His proposed solution, like BAP’s, is the iron fist. He thinks America needs a king, a dictator with total military power, and he offers tips on how a president might become such a kingly king. The plan: Ignore court rulings and laws you don’t like, and maybe have “taped behind your balls, a non-fungible token (NFT) which controls the nuclear deterrent. Now that’s power.”

Swaggering talk about a super-empowered dictator appears to have tremendous appeal to the men of Claremont. In their pseudoclassics way, naturally, they frame it as the rise of an American Caesar. How glorious! Sometimes, the reveries are tucked inside high-sounding language about “statesmanship.” The “man of action” is Claremont’s favorite character in Aristotle, mainly because, as in the case of Christopher Rufo, the former Claremont fellow behind the anti–critical race theory hysteria, the men of Claremont explicitly aspire to become such figures themselves.

What will the manly dictator do once in power, apart from smashing the Cathedral to bits? Yarvin has little to say on that point. Who cares about the morning after? Like BAP, he practices what Nietzsche called “grand politics.” It’s all about magnificent gestures and look-at-me explosions. Details are for the Bugmen.

Anton’s approach to the Caesar question is particularly revealing and provides an example of what Straussianism has come to mean at Claremont. In his 2020 book, The Stakes, along with his appearances on several podcasts, including a two-hour discussion with Yarvin, he frames the prospective rise of a fascist dictator as prophecy, not policy, and insists that he laments such an eventuality. But then he turns around and declares that we have a choice. On the inevitable slide into a post-constitutional order, we can have a Blue Caesar or a Red Caesar. The Blue version—a combination of “Hillary Clinton and Pol Pot,” according to American Mind contributor Charles Haywood—would, Anton writes, rally “all the power centers and commanding heights of our society” to the cause of the “state-directed persecution” of conservatives. The Red one would at least draw from the part of the population with high “social capital,” which is fit to manage the “necessities” of life—this appears to be Anton’s euphemism for Trump-supporting, non-ruling-class Americans. But such a Red Caesar is unlikely, says Anton, because—woe to us!—conservatives are still too weak and disorganized.

Anton pretends merely to offer predictions grounded in wisdom of the ancients. But his target audience would have little trouble deciphering the hidden message for today. “Me, I like, if not love, the idea of a Red Caesar,” gushes Haywood. Nathan Pinkoski, a Claremont fan writing for First Things, the go-to journal for right-wing theoconservatives, explains Anton’s communications strategy: “In good Straussian fashion, what he teaches is not what he says. With great moderation, he explicitly teaches us how to act prudently within the framework of the republican constitution; with great daring, he implicitly teaches us how to act prudently when the republican constitution is gone.” In other words, Straussianism at Claremont means pushing authoritarian fantasies in not-so-secret code while cosplaying ancient philosophers.

So, who gets to join the secret society of latter-day Greco-Roman authoritarians? A strange fact to remember is that Costin Alamariu, a.k.a. the Bronze Age Pervert, got his Ph.D. from Yale. Curtis Yarvin has degrees from Johns Hopkins, Brown, and the University of California, Berkeley. Anton is a graduate of U.C. Berkeley. Their hero Ron DeSantis has both Harvard and Yale on his C.V. Manly man Josh Hawley is Stanford and Harvard. Yes, Virginia, these very men are themselves the Bugmen. When they talk about sticking it to the administrative state or fantasize about having their dictator-buddy tell all the liberals to suck on it, they seem to be dreaming about revenge on the professors, administrators, and fellow students who were mean to them on their way up.

It is with that in mind that one can make sense of the strangest aspect of the Claremont pathology: its obsession with elite higher education.

Adventures in Higher Education: or, Claremont Goes to Florida for Spring Break!

Only last year, the Hamilton Center for Classical and Civic Education at the University of Florida was just an idea on a piece of paper. But it quickly picked up $3 million in state funding, thanks to advocacy from the Council on Public University Reform, a mysterious group whose representative, Joshua Holdenried, previously worked at the Heritage Foundation and has a long history of working with conservative religious causes. The Florida legislature then approved an additional $10 million. According to the Council on Public University Reform’s draft proposal, the center would hold the power to appoint its own staff and educators in classics, history, and the humanities without consulting the existing faculties at the university.

The nonprofit behind the Hamilton operation is headed by a Claremont Review contributor, and the center’s arrival was music to the ears of Claremont’s Florida man, Scott Yenor. A hint about the center’s ideas in civics education may be gleaned from its decision to hire Pinkoski, who took up his position as a visiting faculty fellow at the center around the same time he published a review in First Things of a key text in the white supremacist canon: Jean Raspail’s The Camp of the Saints.

Published in France in 1973, Raspail’s novel imagines the horror that unfolds when one million nonwhite immigrants land on French shores. The subhuman invaders, as Raspail describes them, wallow in their own feces and delight in trampling over the misguided liberals who thought to welcome and feed them. The book has long been a favorite among white supremacists, but Hamilton’s man thinks it is a work of “genius” that exposes the—you guessed it—“cancel culture” and “nihilism” that is stabbing the West in the back. The Camp of the Saints is “the most important dystopian novel of the second half of the twentieth century,” he writes. Move over, Handmaid’s Tale!

The Hamilton Center is one of many such centers springing up around the nation. It is also one piece of DeSantis’s plan for higher education in Florida, along with the makeover of New College. Rufo, the anti–critical race theory guru, now serves as a trustee of New College, the small, liberal-friendly state school that the governor hopes to convert into an ideologically right-wing academy. Joining him on the board, as noted above, is Charles Kesler.

Fortunately for us, Rufo has been as transparent about his plan for the nation’s universities as he was for whipping up the fraudulent hysteria on critical race theory. (“The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think ‘Critical Race Theory,’” he explained on Twitter.) In a lecture delivered in the safe space of Hillsdale College, Rufo revealed that America’s universities—all of them, apparently, with the exception of Hillsdale and a handful of allies—are in the hands of the woke and discriminate rampantly against right-wingers. The time has come, said Rufo, to counter this nefarious tendency with a new, parallel university system that would hire the right people and fire the lefties, and teach a pedagogy more in line with his beliefs.

One person who gets it, by Rufo’s own estimation, is journalist and January 6 conspiracist Darren Beattie, whom Trump appointed to the commission that encourages the preservation of Holocaust sites. Beattie gushes about the results of the program in Florida so far, citing an unsigned piece in Revolver News, a right-wing outlet, that compares the right-wing reconquest of Florida’s university system with Napoleon’s lightning victory over the Austrians in 1805.

Beattie was too far out even for the Trump administration; he was fired after it emerged that he spoke at a conference attended by well-known white supremacists. A listserv for Claremont alumni swiftly accumulated messages of support for Beattie that included some amount of racist and white nationalist commentary, notably from alt-right troll and Holocaust denier Charles Johnson. That prompted some participants holding respectful positions to withdraw from the listserv; eventually, Claremont shut it down. But Johnson himself had been, in fact, a Publius Fellow at Claremont and a contributor to the Claremont Review. And he had scored a flattering foreword to his own book on Calvin Coolidge from none other than his eminence, Charles Kesler.

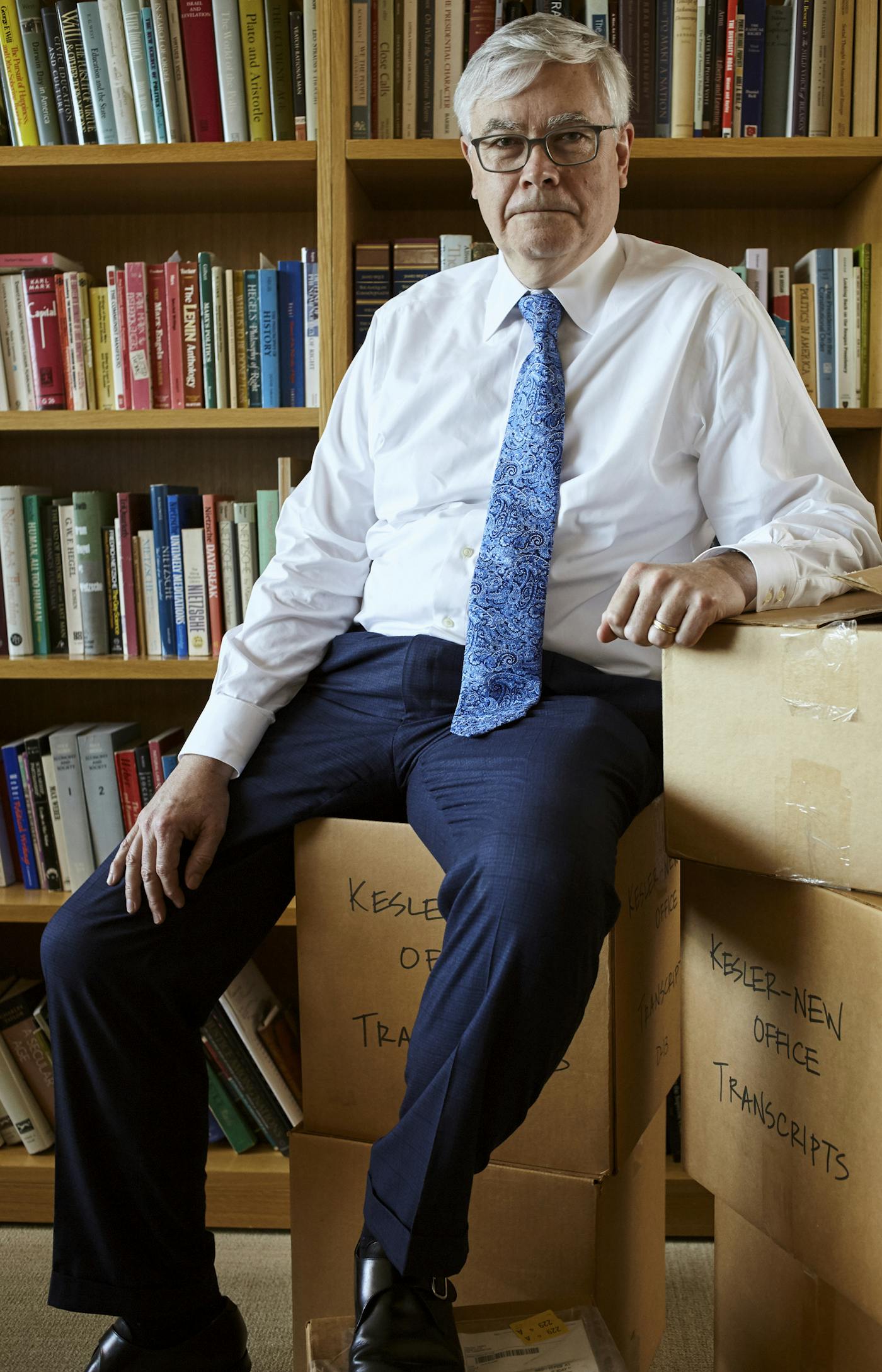

Charles Kesler blames it all on Hegel—and Woodrow Wilson.

BRAD TORCHIA/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX

Why is Claremont helping to normalize white supremacist narratives? The political capital to be made from playing to racial grievance in the Trump era is perhaps too obvious to belabor. It is much more interesting to note that the tendency long preceded the Trumpian turn. The men of Claremont routinely complain, as Kesler does in his Crisis of the Two Constitutions, that the contemporary academy has it in for “dead white males.” It is tempting to dismiss such claims as just another grievance narrative from those living white males who feel themselves to be the true victims of discrimination in today’s America. But this would be to overlook the role that such grievances play in consolidating the Claremont position on intellectual history. In the meta-narrative that Claremont absorbed from Strauss and Jaffa, greatness comes from a distinctive civilizational tradition, one that got its start in Athens, then picked up something in Jerusalem to become “the West.”

The Claremonters generally do not, on balance, explicitly identify this tradition with a racial group. Some are savvy enough to include a smattering of people of color in their narratives (Frederick Douglass being a favorite). But their followers likely have little trouble grasping that the whole point of reviving The Camp of the Saints is to conflate the desire to preserve civilization with the fear of other races and peoples. John Eastman’s views on race may be presumed to be benign, but those of the Proud Boys who stormed the Capitol on January 6 are not. And yet the Proud Boys’ oath could just as well serve as a Claremont motto: “I am a proud Western chauvinist. I refuse to apologize for creating the modern world.”

A truly scholarly history would show that what we call “the West” is the work of human interactions spanning the globe. The fabled Greeks drew inspiration from as far afield as India, and many encounters with different cultures shaped history decisively. It is also clear that not every person who has mattered in the process was white or male. But Claremont doesn’t do intellectual history, properly speaking. There is a better name for what it does do, and that is identity politics.

Claremont has had few qualms about pursuing its version of identity politics across the board. Affirmative action is just fine, according to Claremont’s Florida model, as long as it is used to boost the kind of people who make the right sort of noises about the “gynocracy” and demonstrate an interest in white supremacist novels. The administrative state is a good thing—provided you can funnel taxpayer money to ideologically correct centers of learning. Meritocracy is the great American ideal, but only when “merit” is defined as advocating for what your ultrarich patrons already know to be true. Cancel culture is a good thing, too, as long as you are using state power to ban books you don’t like.

To be sure, there are some excellent critiques to be made of diversity programs, and maybe some of these critiques make it through the apocalyptic rhetoric coming out of Claremont. What you won’t hear, however, is any serious consideration that such programs came into being to address real problems in a diverse society with a long history of racial oppression and rank discrimination. That’s because the men of Claremont aren’t here to propose practical policy solutions to the problems facing America. They come to rile up a grievance-addled base and satisfy their own resentments—and to raise enough money to keep the circus on tour.

They Don’t Shoot Administrative States, Do They?

In his Crisis of the Two Constitutions, Kesler names “the administrative state” as both the ideal of “Progressivism” and the font of all evil. He appears to have borrowed most of the argument, along with the strange fable about Hegel and Woodrow Wilson, from John Marini, a senior fellow at the Claremont Institute whose association with the organization goes back to its very beginnings in the 1970s.

The critique of “the administrative state” has a long history and touches on issues of concern in any modern democracy. As noted by Dwight Waldo, the subtle political theorist and onetime federal official who brought the idea to attention in a 1948 book, the administrative apparatus of the modern state has emerged as a new and powerful political function, distinct in important ways from a traditional conception of the legislature and executive. The administrative state often attempts to justify its power through an ideology valorizing scientific efficiency and managerial expertise. Yet, as Waldo points out, government administrators engage in inherently political tasks; they seek negotiated solutions among constituencies, and they ultimately answer to a democratic people through their elected representatives. The sensible critique of the administrative state, then, is a complicated one. The point isn’t to destroy it—surely we’ll want to hold on to the air traffic controllers and food safety inspectors—but to ensure that it remains accountable to the people in a democratic polity.

But the Claremont Institute doesn’t do complicated, and Marini is a case in point. He is a black-and-white kind of thinker, and one can get a sense of where he locates the color line from his analysis of Donald Trump’s candidacy for president in 2016. Marini lauded Trump for his interest in “unifying the country” by “appealing to the common good.” And “Trump has appealed to the rule of law and has attacked bureaucratic rule as the rule of privilege and patronage.” In brief, Trump represented “an existential threat” to the administrative state, according to Marini, and the secret reason why many progressives oppose Trump is that they love nothing more than the smell of bureaucracy in the morning.

In Marini’s narrative, the administrative state is not to be reformed; it is inherently illegitimate. “The tacit premise of the rational state, and the defense of the administrative state,” he claims, “rests upon the assumption that the power of government cannot be limited,” which, in his reading, directly contradicts the wisdom that the Founders supposedly gleaned from Aristotle. Consequently, as his co-author, editor, and fellow Claremonter Ken Masugi writes, “The administrative state is the modern face of tyranny—an issue on which thinkers as diverse as Leo Strauss and Carl Schmitt apparently agree.” The references are apt indeed. Marini’s critique of the administrative state, and even his identification of Hegel as its evil mastermind, tracks Schmitt’s critique of the liberal (Jewish) order with uncanny precision.

So who, according to Marini, is to blame for the rise of the administrative state in America? Marini’s answer: The “knowledge elites in the bureaucracy” who have manipulated public opinion in a dastardly plot to advance their bureaucratic power. Shorter Marini: The Bugmen did it. So what are we to do about air traffic, food safety, the environment, defense? Who knows. Details. Go ask the Bugmen.

Four years of the Trump presidency afford us some insight now into what the “deconstruction of the administrative state,” to borrow Steve Bannon’s phrasing of the Claremont idea, looks like on the ground: epic levels of corruption, nepotism, incompetence, polarization, and politicization. The best illustration of the tendency, as it happens, comes from the tenure of Claremonter Michael Pack as head of the U.S. Agency for Global Media (whose flagship is Voice of America). Pack was president and CEO of Claremont Institute from 2015 to 2017. His reign at Voice of America began late in Trump’s term, lasted seven months, and ended two hours after President Biden took office. During those seven months, Pack “inspired multiple formal investigations and rebukes” from various federal and D.C. judges who found that he acted “illegally and even unconstitutionally,” according to NPR reporting. “I don’t think he had a plan other than to just blow the place up,” said Dan Hanlon—a former top aide to Trump’s chief of staff who was himself appointed by Trump to the agency. “We would come in at nine o’clock and stamp out at five o’clock,” Hanlon said. “And we played foosball all day. And we would just sit there, commenting about how absurd this whole thing was.”

Broadly speaking, the kind of anti-government nihilism that Marini preached and Pack practiced has two natural constituencies. The first consists of those people who generally do not suffer from discrimination and who, unaware of the role of the administrative state in creating and sustaining their privilege, see no place for government in securing their civil rights. The second consists of those economic interests whose activities cause harm (such as pollution or the degradation of communities) or depend on monopoly profits, and who therefore do not wish to be regulated. The Claremont Institute fills its rosters with members from the first group but fills its coffers with representatives of the second. If you want to understand the Claremont Institute phenomenon, the oldest adage of journalism is indispensable: follow the money.

What Money Buys When It Thinks It Is Buying Ideas

Apart from whatever small dollars it wrings from anxious recipients through its mass mailers, the Claremont Institute appears to get the largest chunk of its money from Tom Klingenstein, the New York–based finance executive who serves as its current chairman.

Claremont has other funders, too. The Sarah Scaife Foundation, the Bradley Foundation, Donors Trust and the Donors Capital Fund, and the Dick and Betsy DeVos Family Foundation—all have chipped in. These are among the same groups that top the list in funding climate science denialism; the privatization of public education; the reduction of taxes for the rich, especially of inheritance taxes; and other causes known to warm the hearts of billionaires.

Thomas D. Klingenstein, a main Claremont financial backer.

NATALIE IVIS

The direct funding from ultrawealthy interests is really only part of the story of how money has made Claremont. Claremont heroes such as Ron DeSantis, Josh Hawley, and J.D. Vance are to an important extent creatures of the donor class. The money that these political leaders receive from their wealthy friends turns into power for Claremont.

It would be a simple story if the money flowing to Claremont was merely there in pursuit of financial self-interest—and to some extent it is. Many of the donors would love to deconstruct the administrative state, after all, since it stands in the way of many of their privileges and moneymaking activities. So they will put up with the raw eggs, the Bronze Age nuttery, the woman-hating, and all that, as long as it delivers lower taxes and “small government.”

But what can history tell us about this kind of compromise? What will happen to the moneyed interests if BAP gets his military dictatorship, or if Anton’s Red Caesar steps forth?

I put the question to Steve Schmidt, and he lit up with enthusiasm. He urged me to read a speech that Hitler gave in 1932 in Dusseldorf to an audience of business executives. Hitler makes an explicit argument against democracy, he said, and “it’s not an unsophisticated argument—it’s what Tucker Carlson said every night on Fox and now on Twitter.” The core of the argument, in its American form, is that “America needs a Caesar.” Why does America need a Caesar? “To protect freedom and liberty—because democracy threatens the privilege of those who ‘built the country,’” Schmidt continued: “All fascist movements require the cooperation and capitulation of conservative movements. The conservative party is the party that is devoured by fascism in any type of right-wing fascist descent.”

Having spent a fair amount of time exploring the mind of Claremont in preparation for this piece, I find Schmidt’s analysis extremely convincing. It does, however, leave me with a loose end that I think of as the Klingenstein problem. When we suggest that conservatives are cooperating with and capitulating to authoritarians, we are supposing that they still see the alliance in rational, transactional terms. We implicitly assume that they know that they are making a pact with the devil, and we fault them for a moral failure or perhaps a lack of foresight. But that doesn’t describe Klingenstein at all. He clearly has been drinking the same Kool-Aid that was intended for the working classes. He isn’t capitulating to the forces that promise to destroy the foundations of his own wealth and privilege; he actively wants to become one with them.

The kind of authoritarianism that Claremont is peddling did not happen to the conservative movement by accident. It is the predictable result of the massive investment that conservative money made over the past 50-plus years in polluting American political discourse with its massive complex of ideological factories. When you spend enough to spread unreasonable ideas, you will get an unreasonable society. You might even become a bit of a crank yourself. It goes back to a problem at least as old as Plato. If your power depends on lying to the people, that doesn’t make you noble. It just leaves you with a choice: Accept that you are a fraud, or embrace the lie.