As we honor labor today, the

upsurge in union organizing at Amazon, Starbucks, Hollywood studios, and

hotels seems distant from controversies about affirmative action

and legacy admissions at elite colleges. News stories and commentary on unions and universities

have missed a connection between them that sometimes strengthened American civic culture and politics for at least a century. Since at least

World War I, some legatees of Ivy League privilege have deployed their

advantages to oppose injustices and support workers, often against these defectors’ own comfortable families’ and college classmates’ interests, and

often at some risk to themselves.

Their personal conversions and political trajectories have

mattered because they’ve known the “upstairs” of the American household as

intimately as they’ve come to know the “downstairs.” Yet they’ve often been

forgotten, as George Orwell might have been had his account of being Down

and Out in Paris and London not been surpassed by the novels that

cemented his legacy and fame, Animal Farm and 1984.

In 2005, disgusted by Ivy-heavy triumphalism about the war

in Iraq, I searched in Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library for examples of

wiser civic-republican leadership by scions of privilege who’d transcended and

sometimes sacrificed their own prospects to strengthen the republic, not the

plutocracy. One of them, Thomas William Lamont II, would have been an uncle of

Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont had he not left Harvard as a freshman to fight

fascism in World War II, only to die in a submarine that was lost off the coast

of Japan nine years before Ned Lamont was born. I profiled him in The American Prospect in 2006.

I should also have profiled then an even more highly instructive

example of labor and civic leadership set by Malcolm H. Ross, a son of an “old

stock,” prosperous family, who graduated Yale in 1919 but plunged into

years of body-wracking labor alongside miners and oil drillers and became a New

Deal official with the National Labor Relations Board. In 1939, Ross

published Death of a Yale Man, a memoir-cum-report-cum-jeremiad

that’s a worthy companion to Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London and

his Homage to Catalonia. Ross’s book is especially instructive for Americans

right now, amid today’s organizing efforts, strikes, and controversies over

elite college admissions.

When I discovered Death of a Yale Man in 2005, leaders

of the “global war on terrorism” and on “Islamo-fascism” included President George W. Bush

(Yale class of 1968); Vice President Dick Cheney (Yale dropout, ’61); Iraq Coalition Provisional Authority administrator (i.e., proconsul) L. Paul Bremer III (’63);

CIA Director R. James Woolsey (’68. Bush’s Yale classmate); Director of

National Intelligence John Negroponte (’60); Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul

Wolfowitz, who as a Yale political science professor had taught Cheney’s chief

of staff I.L. “Scooter” Libby (’72); Bush’s “axis of evil” speechwriter David

Frum (’82); Reagan State Department veteran Robert Kagan (’80); Kagan’s father,

the Yale historian of ancient empires Donald Kagan, a fervent Iraq War booster;

and former New Republic editor Peter Beinart (’93), a noted Iraq War hawk who later recanted that position and whose book The Good Fight seemed to say it all.

Some Yale undergraduates whom I was teaching at the time

were all in with the crusade: some headed to Special Forces, others to pro-war

think tanks. But few of them understood how deepening inequalities and

unjust, injurious working conditions at home were weakening the misadventures

abroad. Yet those failed, top-down crusades, not only in Iraq and Afghanistan

but also in Cuba and Vietnam, have always prompted a few heirs of privilege to

challenge their elders’ premises and practices. Even World War I, which Ivy

leaders from Woodrow Wilson on down presented as “the war to end all wars” and

“to make the world safe for democracy,” seeded only more wars and fascism and

prompted the disillusion but also the dedication of people like Randolph Bourne

and Malcolm Ross.

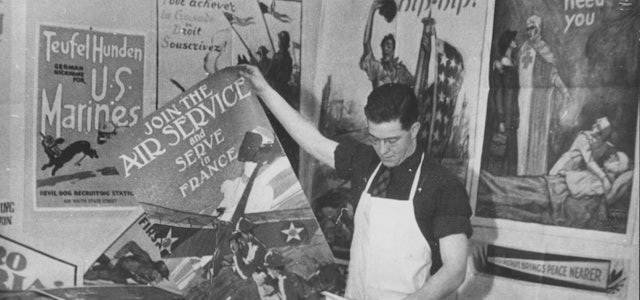

After a

short stint as a bond salesman upon graduating from Yale in 1919, Ross worked

as an oil-field driller in Texas and a copper miner in Kentucky. Later, he

became the public information officer of the NLRB, from 1934 to 1940, and then chair of FDR’s Federal Fair Employment Practice

Committee (now a commission). Because Ross, like Orwell, was a product of elite

schooling, he depicted knowingly the downsides of being elevated at others’

expense and the upsides of a conscience-driven dedication to fighting for

workers whose “attempts

to speak for themselves through organizations were being bitterly and

successfully opposed by another kind of people I knew—the kind with whom I

had gone to Hotchkiss and Yale.”

William

Jennings Bryan, the “Great Commoner,” running for president in 1896, had told a

Yale audience that “99 out of 100 of the students of this university are the

sons of the idle rich.” Two decades later, Ross, by then himself a Yale

student, cited Bryan’s charge, noting that ‘‘nine out of 10’’ of his fellow

students subscribed ‘‘to anti-labor attitudes with fervor.’’ A few dissenters

supported the labor-friendly, immigrant “settlement house” movement, but “more

common were those who thought that modern society was ‘rotten with altruism.’”

When he was working with the NLRB and the Fair

Employment Practices Committee in the 1930s and early ’40s, Ross noted that his Hotchkiss and Yale

classmates who’d become company lawyers contesting the government’s “rotten

altruism” toward workers and the poor believed that

the

technique of opposition to [banning child labor] imposes a necessity to avoid

the directly sentimental issues of hollow-eyed children and instead to find

another sentimental plane such as the preservation of the popular concept of

what the Founding Fathers held dear [such as a lone worker’s supposed right to

work or not] to brandish at judges who by the nature of their craft sit in terror

of rendering decisions out of key with the revered past.

Ross described that “revered past” and

its sequels not reverently but morally, even when doing so entailed judging

himself:

Our

Revolution was fought for the right to have and to hold. Our later genius was

to lie in making more possessions than any people on earth had ever before

enjoyed, and with our skill in production came necessity to distribute widely,

to create new desires, and to speed obsolescence so that there might be a

market for almost-new things.…Private ownership and

many things to be owned—these two formed a pact of mutual security and on

their payroll placed art, music, and the drama. Forever before our eyes we had

seen advertisements linking the good and the beautiful with things we would

like to own.…The car I drive owns my

enthusiasms as a swift and gallant mechanism, and so in turn the car must own a

part of me.… Only with an effort can I raise in my mind a picture of the men

who dig the ore and coal, roll the steel, saw the lumber, tan the hides,

fabricate the bolts.

Although the bones of this

passage carry a Marxist critique of commodity fetishism that Ross picked up

from books and pamphlets and union organizers, the word-flesh on the bones of

his passage carries not folksy agitprop but his personal, “old stock” American

sensibility. He brings his structural economic and political reckonings to the

touchstones of direct experiences in mines and oil fields and of his own

“elite” training for republican guardianship. The tension between them carried

him to a fateful life decision:

A

choice was presented during the past few years, between betting on paternalism

as a way of life, or standing with the tough-fibered, earthy, sometimes brutal,

often ignorant men and women who have been taught by living to hate

paternalism. I think their instincts are right. I would like to see America try

democracy at whatever cost to comfortable people. And because I know the

strength of the opponents of authentic democracy, I have decreed the death of

what I was.

The “death” in Death

of a Yale Man isn’t physical but spiritual, and it presages rebirth.

Dying unto one’s former self to be born anew is a Christian trope, but other

societies enact something like it in what anthropologists call “rites of

passage,” which guide youths from childhood innocence to adult membership in

intergenerational communities by putting them through death-like eclipses of

their childhood interests and then through arduous tests of their emerging public prowess

and communal dedication, under the gaze of respected, ratifying elders. But,

like Orwell, Ross put himself through tests that his own elders weren’t

demanding of him.

Effective dissent like

that, whether it’s made by an Old Testament prophet, a shaman, a Nathan Hale or

Tom Paine in British America before the Revolution, or by an Orwell or a Ross,

isn’t driven mainly by bitterness and revenge. It carries affirmations—“I

would like to see America try democracy at whatever cost to comfortable people”—that the dissenter expresses in new or altered prophecies or “constitutive

fictions” that others can listen to, learn from, and love.

Ross is almost startlingly

prophetic in some passages. He anticipated environmental and technological

challenges that few acknowledged in the late 1930s:

Someday … I shall have to tell my son, who was not born when I began writing this book … that the conquest of the forests left bare slopes so that rivers … run mad to

kill people and destroy their farms.… [O]n a new frontier, he will have to

learn of the fight against machines which in curious ways have turned against

their inventors.

David Chappell, one of

the only historians in our time who has rediscovered and written about Ross,

notes in A Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion

and the Death of Jim Crow, that Ross was “one of

the first non-Southern liberals to gain experience in racial politics” as well

one of the first to write about his fellow white miners and drillers swooning in desperate raptures at

fundamentalist tent revivals led by itinerant preachers such as Billy Sunday in

Kentucky. Chappell quotes Ross’s ironic observation that

“there is a certain dignity about anyone

entirely engrossed in his profession, and Billy was a knockout at the business

of saving, pro tem, the souls of the emotional.”

Ross’s liberal cynicism

about evangelical religion kept him from developing religious commitments of

his own. But through his own irony he could yearn, “Lord of Hosts, if thy

servant Billy Sunday had been a man with an honest tongue to tell people where

they stand and to what cause they should deliver their hearts, what a healthy

jolt those meetings might have given Louisville.” That the coal miners’

suffering never came up when Billy Sunday was in town, largely because he was

in town, “illustrates our traditional preference for emotion over realities.”

By forsaking ample rewards

for conforming to the conventional protocols that had been prescribed for him

in his youth, Ross developed a realistic, not “emotional,” manner of dissent,

strengthened by advantages he’d inherited but also by disadvantages he’d

embraced:

He who

lives among working people has to make his own way. No clothes, no manners, no

position, no reputation can help. There is no log-rolling [in other words, no

mutual back-scratching], no membership in clubs.… For the standards of those who

live without pretense are stripped bare of any values except what you yourself

are. That is, the unsophisticated you, deprived of all glamorous aides. That

cruel unflattering light, I suppose, is democracy. Many people in their hearts

despise or fear it.

Although Ross probably

never met or even read Paulo Freire, the Brazilian, Christian socialist

philosopher and educator who was 20 years younger than he, Freire’s great book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, contains passages that

could have been written, almost word for word, by the author of Death

of a Yale Man, who certainly lived by Freire’s words: “A real humanist

can be identified more by his trust in the people, which engages him in their

struggle, than by a thousand actions in their favor without that trust.”

“My life,” Ross reflected

(almost as if he were responding to Freire!), “has been a constant oscillation

between feeling superior and being bumped into reality by the obvious courage

and mentality of people a peg or two lower in the economic scale.” Most Ivy

League graduates are somewhat insulated from the “constant oscillation,” whose

mixture of conceits and good intentions Ross captured well:

A

pleasant culture thrives in soil perennially watered by profits from absentee

ventures. Cherishing their way of life, the established families of the 1890s

and early 1900s closed their eyes to the crude operations through which wealth

passed before it was refined into money. This was not itself a mark of

heartlessness. It was a nice question in ethics, that matter of building up a

family’s comfort and security on profits siphoned by finance from the great

pool of human labor. Near at hand were a man’s first responsibilities—his

career, his home, his children.… Remote from his sight and experience,

belonging to a class he could easily believe less deserving than himself, were

the muckers, the puddlers, the mule-skinners, the bohunks, the roustabouts.… The head of the family thought of these men occasionally, and with a faint glow

of pride at his own capacity for sympathy. And who could criticize him for

sticking to his career instead of begging for ridicule by tilting at social

windmills?

Who, even now, would

criticize the head of a privileged family for sticking to his career while

posting a “Black Lives Matter” sign on a website or a spacious lawn instead of

taking time to try to reconfigure an untrustworthy police department, a

corporate workplace, a school curriculum, or a particular affirmative-action

protocol? In a “pleasant culture” of privilege—like the one that I enjoyed

at the fiftieth-year reunion of my own Yale Class of 1969 in 2019 on the college’s

Old Campus, the very spot where Ross and his own Yale Class of 1919 had known

one another a century earlier—it isn’t often acknowledged that today’s

union-busting efforts and white-supremacist violence aren’t much different from

what he witnessed, reported, and resisted. Most at my reunion in 2019 were

all in with honoring our own classmate, the private equity emperor Stephen

Schwarzman, as

a benefactor and visionary of the university, of America, and of the

world. Most in Ross’s class would have done the same.

Few would have endorsed

what Franklin D. Roosevelt told tens of thousands who rallied to his

reelection campaign in 1936 in New York City’s Madison Square Garden, where,

three days before the election, FDR spoke words that Ross surely read and

endorsed:

For

twelve years this nation was afflicted with hear-nothing, see-nothing,

do-nothing government.… We had to struggle with the old enemies of

peace—business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking, class

antagonism, sectionalism, war profiteering [which] consider the government of the

United States as a mere appendage to their own affairs. We know now that government

by organized money is just as dangerous as government by organized mob.

Even

fewer members of Ross’s Yale Class of 1919 can have endorsed Abraham Lincoln’s

assertion, which Ross quotes in Death of a Yale Man’s concluding

chapter: “Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only

the fruit of labor and could never have existed if labor had not first existed.

Labor is the superior of capital and deserves much the higher

consideration.”

The book should be read by every student and alum of elite colleges and law schools. Unfortunately, it’s hard to find, except

in a few libraries that have kept it. I’m grateful that it was ever published at all.