Today there is no slavery to avoid, of course, but the revived Whig Party would not likely lead the nation on matters related to race or diversity. But nor would it likely promote itself, as today’s Republican Party does, through the exploitation of racial animus. A revived Whig Party would also not likely promote taxation of businesses and the rich. But it would likely be more open to compromise with Democrats on taxation in order to keep the federal budget solvent, something today’s Republicans have no particular interest in doing. One especially refreshing aspect to reviving the Whig Party is that conservatives would no longer pretend to represent the working class, creating an opportunity for Democrats to recapture that constituency.

The Whig platform of 1844 (when it ran Clay, unsuccessfully, for president; he lost to James Polk) has a remarkably contemporary ring. It called for

a well-regulated currency; a tariff [today Whigs would say “tax”] for revenue to defray the necessary expenses of the government, and discriminating with special reference to the protection of the domestic labor of the country; the distribution of the proceeds of the sales of the public lands; a single term for the presidency [again: bad idea!]; a reform of executive usurpations;—and, generally—such an administration of the affairs of the country as shall impart to every branch of the public service the greatest practicable efficiency, controlled by a well regulated and wise economy.

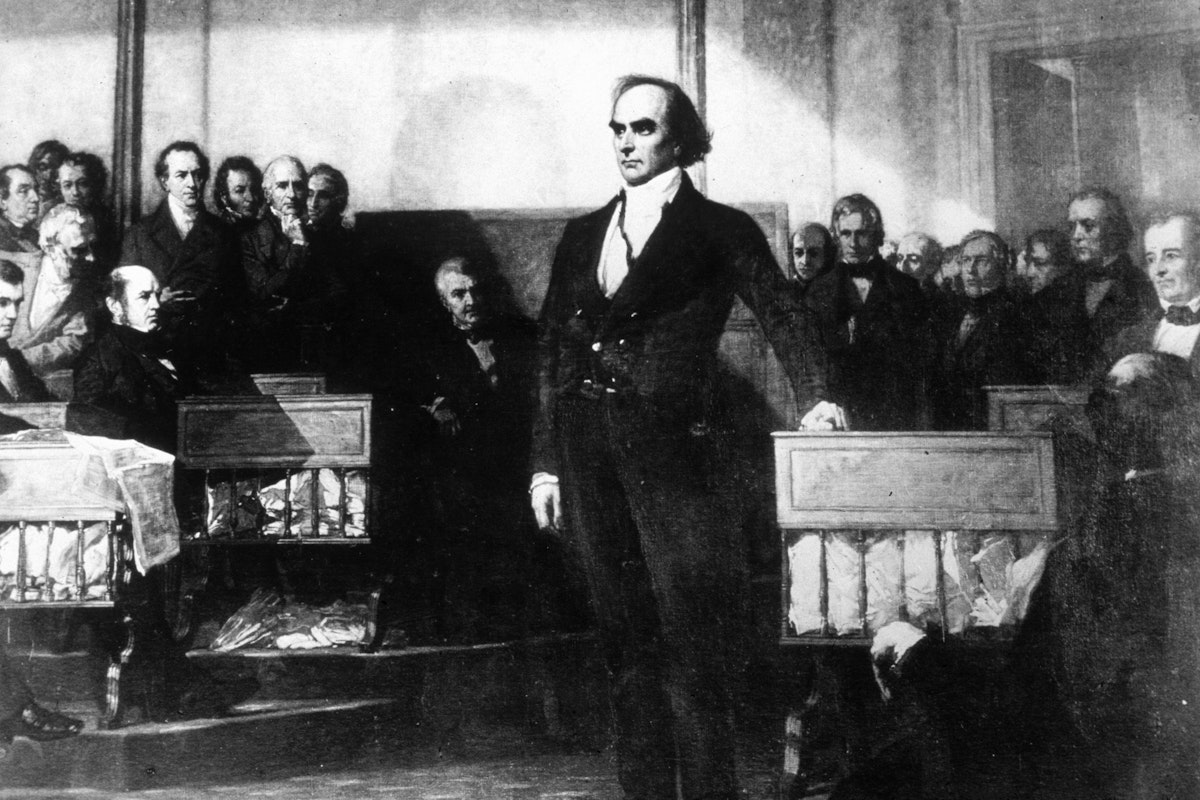

“I’m a Whig,” David Brooks wrote in 2018, and he is. He’s always been conservative, but he’s never been especially anti-government. In the late 1990s Brooks and Bill Kristol advocated something they called “national greatness” conservatism that looked a lot like Whiggery. They called for a return to “the nationalism of Alexander Hamilton and Henry Clay and Teddy Roosevelt.” They called for a more energetic federal government and dispensed with certain conservative orthodoxies such as banning abortion. The idea foundered mainly because of its emphasis on military intervention (a doctrine, Wilentz notes, more in line with Bull Moose Republicanism) which came to grief in Iraq. But even here the Whig example is instructive, because the Whigs resisted militarism, most notably when many of them opposed Polk’s Mexican War.