Inside

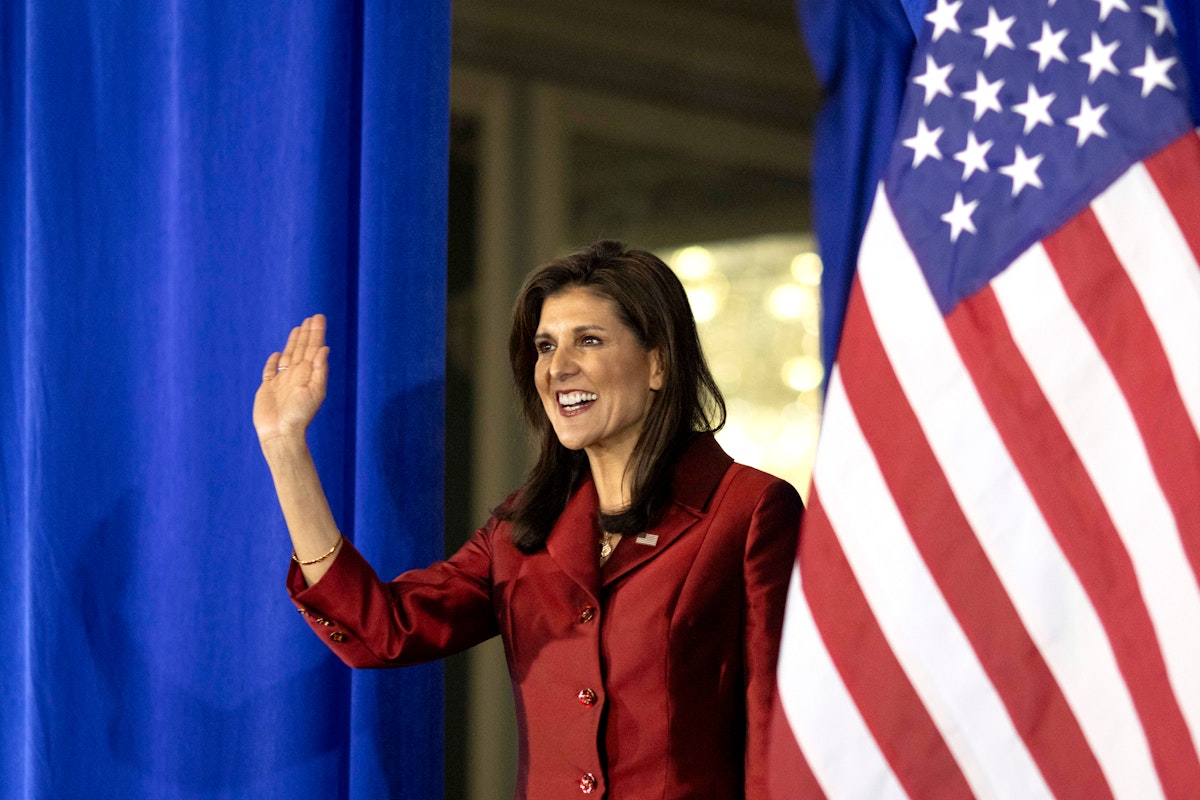

the Grand Ballroom, Haley appeared not a puppet as much as an actor playing the

part of an ambitious striver in a Netflix show about U.S. politics. She offered

a little of something to almost everyone. Anti-Democrat signage and rhetoric

was conspicuously absent, and the indications are that at least some of the

votes she got in South Carolina were that of Democrats and independents. She

was a moderate, a healer, and she would fight for “all of America,” she

claimed. She was offering a real choice, something other than “four more years

of Biden’s failure” and “four more years of Trump’s lack of focus.” She was a

woman for women, a military spouse for the military, and the child of

immigrants from India resolutely opposed to the “nine million illegals” with

“enough fentanyl to kill every single American.”

She

spoke for 15 minutes and stayed about as long to mingle with the crowd. Among

the Charleston rich, almost entirely white, there was a sprinkling of sleek Indian

faces. I spoke to one of them, a suave gastroenterologist who described himself

as an independent and who had known Haley from well before her entry into

politics. He had voted for Trump in 2016 and 2020, he said, and he had come to

regret that. But Biden wasn’t “all there,” Kamala Harris was “useless,” and it

was Haley he now pinned his hopes on. The child of an Indian diplomat who had

immigrated to the United States in 1989, he was utterly opposed to the open

border and the “illegal aliens” crossing it with impunity. “We all came here

legally,” he said. That was a crucial distinction.

It

made sense that the wealthy, upper-caste Indian elite would gravitate toward

Haley. Born to affluent Sikh immigrants as Nimarata Nikki Randhawa, Haley has

reinvented herself as a Southern white person. She is pro-military, pro-empire,

pro-Israel, pro-Narendra Modi, pro-business, anti-union, and anti-abortion. The

word race wasn’t mentioned once in her speech, but that too was in keeping with

her position that business is more important than confronting South Carolina’s

long, ongoing history of violence and immiseration against its Black

population. Robert Greene II, an African American professor of history at

Claflin University in Orangeburg, was present at the state capitol in Columbia on

July 10, 2015, when, in the aftermath of Roof’s massacre at Mother Emanuel

church, the Confederate flag finally came down. Haley, Greene pointed out to

me, had just the previous year—she was running for a second term as governor—said

that the Confederate flag wasn’t an issue since no business had complained

about its presence at the state capitol.